The Dominican Republic is united like no other event could unite

them. It’s the international baseball tournament and they are hoping to

win again after the undefeated 8-0 run to the championship in 2013. On

my weekend trip to the capital, every TV set there and in the city of

San Juan de la Maguana was tuned into the tournament. Baseball is the

national sport (well, apart from dominoes) and everyone is following

along looking forward to the moment of victory.

Backing up a bit,

the baseball team here is the shining gem in the community. Last year

Bridges (the company I am working for here) got a member of the

community to donate a piece of flatish land to the youth center they

were building. After making it much closer to flat, they installed a

backstop as well as cement stands on both sides. Though far short of

even the most rundown fields in suburban US, it is unequivocally the

nicest field in the area. Between the field and the 40 donated gloves,

catcher’s equipment, and real bases, the youth of Derrumbadero have the

most luxurious baseball set up for miles. And they play like a team that

has won divine favor.

I’ve been to four or five games so far,

and Derrumbadero has won every single one. The first game I witnessed I

only saw the last three innings (they play 7 innings here), where we

went from losing 4-3 to winning 7-4. The second, we came from behind 3-0

in the first to blow out the other team 17-10 or so. The third, I

played first base for the first four innings, as it was the younger kids

and they wanted to show off their Americano (my first game of baseball

ever!!!) We came from behind 5-0 to win it 7-6 with two runs in the

final inning. Next came a sunny Sunday game that gave me terrible

sunburn on my legs but was worth every second of pain. We got down 7-0

in the first two innings and then suddenly turned on the power. By the

fourth, we were up 8-7, and after getting up 15-7, coasted to a 16-12 or

so win.

There are around 50 or 60 kids in the town who play on

the two teams. There is little here in the way of adult supervision,

role modeling, or attempts to build life-long learners out of the

children. However the two managers of the teams are somewhat remarkable

in how they run things. At once fun and firm, these young men are only a

few years older than most of the players, and the same age as some of

them. At 22 or 23, they are both part time students at a university a

hour or so away. They keep track of the lineup, hold onto the extra

baseballs so they don’t all disappear, and most importantly enforce team

spirit and make sure the boys are all building each other up instead of

fighting. One of my favorite moments watching one of the managers,

Xavier, was when he got dressed down by the only father who ever watches

(presumably because he had a broken arm, as I haven't seen him since

his cast came off two weeks ago) because he had let two of the boys tell

another boy that he hadn’t run hard enough for first base. The father

insisted that teams don’t treat each other that way and that it was

Xavier’s job to make that happen. Xavier took this lashing with his head

held high and then replied that the father was right, he’d made a

mistake, and it wouldn’t happen again. And true to his word, the next

time something like that happened at a game that weekend, Xavier called a

pause in the game, got the whole team around him, and told them they

were one group and one family, and if someone needed to be told

something like that, he would be the one saying it.

After the

Dominicans came from behind 5-0 to defeat the USA, I admit I was a

little upset, since I like winning. But I was also excited, for another

win on the world stage at baseball would be great for the DR! I hope

Platano Power takes them all the way to another undefeated championship!

Empowering Millennials through Blunt Analysis of the Systemic Faults of our Predecessors and Ourselves

Showing posts with label conflict resolution. Show all posts

Showing posts with label conflict resolution. Show all posts

Wednesday, March 15, 2017

Thursday, February 2, 2017

Using Emotions to Temper Decisions

Our days are filled with decisions. Some are important, but most just involve the minutiae of what we eat, wear, say, or do. Chances are you don't even notice many of the decisions you make each day. How we decide is a combination of our emotional state and our logical expectations about the social and practical functionality of the options. As a culture, we are against deciding things entirely because of emotion. This comes from Enlightenment thinking, colonial survivalism, and the threat of extinction due to an overly emotive leader with access to nuclear warheads.

Modern consumers are subjected to a daily barrage of surreptitious emotional messaging designed to make us buy things we don't need, but surely want. Two recently effective advertisers have been Apple and Coca-Cola. Apple sold "cool" for many years when the iPod and iPhone first came out, while Coca-Cola still has a stranglehold on the idea that when you open a can of coke, it brings happiness, family, and unbridled joy.

These nuclear and consumption based reasons might make you hesitate to ever use emotions when making decisions. However, I think that there is a space where you can use your emotions to make incredibly effective decisions.

We tend to ignore metallurgy in our expressions about 'temper.' People 'lose' their temper, can be in a 'bad' temper, or can have a 'fit' of temper. When talking about metal, it means to harden by heating and cooling. Imagine if we spoke about our emotions in terms that involved self control, strength, and conditioning, rather than unbridled fire. A blacksmith knows that a low and slow temper produces the hardest and brittlest metals while a hot and fierce temper produces softer, more flexible metal. So when you "lose your temper" it means you've lost control of your temperature and are either too hot or too cool.

When you are making important decisions, they should involve logical assessments about the costs and benefits of each option. This analysis should compare and contrast the short and longer term effects as well as who will be effected. One common method parents teach their children for important decisions is a pros and cons list. This involves a logical and equivalency based approach to deciding.

One of the most important decisions we make each summer at camp is our cabin assignments. Many camps assign their counselors different cabins based on seniority, or allow them to apply for a specific age group. Since our camp is small, and puts so much weight on community, we wait until most of the way through our staff training week before assigning cabins. Each cabin gets two counselors, who live and work together for the following 8-weeks.

This decision process always has a similar formula, but feels very different depending on the temper of the administrators. We will try to figure out the cabin pairings for one gender, then when emotions are overtaking logic, we switch genders. It takes 2-3 passes to get to a point where everyone is comfortable with the cabins. Sometimes the process can get contentious, and erupt in shouting and crass words. Far more often it is a passionate but reasoned discussion where we try to use our feelings about individuals, their histories and prospects, and the needs of the campers and camp to combine into a logic storm of happy goodness.

This decision is made without a time limit (besides getting tired) and with the promise that we will be unified at the conclusion. So while the stakes are high and potentially the success of the whole summer program lies in the decision, we can take our time, think things through, and rely on our cumulative wisdom to find a good solution. In this way, we can let emotions temper our decisions.

In an emergency, two things you don't have are time and the ability to come to consensus. You need a plan and a straightforward set of directions so that you can produce the most reliably good result that helps the most people and hurts the fewest. To prevent rash decisions you should bottle up your emotions during a crisis. Despite this, emotions have an important role to play in emergencies.

In general emotions are more useful in situations where there are multiple possible correct decisions, each with marginal benefits. We use a system of values to guide us in how to apply our emotion. If we feel strongly about something it may mean a particular solution’s marginal benefits should be chosen or discarded.

For 10 months spanning 2009 and 2010 a friend and I prepared for a 5-week trip to the Alaskan Bush. We weighed gear, compared caloric contents of various substances, and read volumes on wilderness survival and Alaska. We also created an emergency plan. We listed as many potential emergencies as we could, and then, from the calm of our own computers thousands of miles apart, debated and doctrinized our responses. This method allowed us the chance to inject emotion and values into our emergency responses without accessing that emotion during the emergency. We had already agreed what we do if one of our backpacks gets washed downstream, or if some of our food spoiled. This meant that as frustration or anger or hunger clouded our vision on the trip, we would still have the tempered response available.

Modern consumers are subjected to a daily barrage of surreptitious emotional messaging designed to make us buy things we don't need, but surely want. Two recently effective advertisers have been Apple and Coca-Cola. Apple sold "cool" for many years when the iPod and iPhone first came out, while Coca-Cola still has a stranglehold on the idea that when you open a can of coke, it brings happiness, family, and unbridled joy.

These nuclear and consumption based reasons might make you hesitate to ever use emotions when making decisions. However, I think that there is a space where you can use your emotions to make incredibly effective decisions.

We tend to ignore metallurgy in our expressions about 'temper.' People 'lose' their temper, can be in a 'bad' temper, or can have a 'fit' of temper. When talking about metal, it means to harden by heating and cooling. Imagine if we spoke about our emotions in terms that involved self control, strength, and conditioning, rather than unbridled fire. A blacksmith knows that a low and slow temper produces the hardest and brittlest metals while a hot and fierce temper produces softer, more flexible metal. So when you "lose your temper" it means you've lost control of your temperature and are either too hot or too cool.

When you are making important decisions, they should involve logical assessments about the costs and benefits of each option. This analysis should compare and contrast the short and longer term effects as well as who will be effected. One common method parents teach their children for important decisions is a pros and cons list. This involves a logical and equivalency based approach to deciding.

One of the most important decisions we make each summer at camp is our cabin assignments. Many camps assign their counselors different cabins based on seniority, or allow them to apply for a specific age group. Since our camp is small, and puts so much weight on community, we wait until most of the way through our staff training week before assigning cabins. Each cabin gets two counselors, who live and work together for the following 8-weeks.

This decision process always has a similar formula, but feels very different depending on the temper of the administrators. We will try to figure out the cabin pairings for one gender, then when emotions are overtaking logic, we switch genders. It takes 2-3 passes to get to a point where everyone is comfortable with the cabins. Sometimes the process can get contentious, and erupt in shouting and crass words. Far more often it is a passionate but reasoned discussion where we try to use our feelings about individuals, their histories and prospects, and the needs of the campers and camp to combine into a logic storm of happy goodness.

This decision is made without a time limit (besides getting tired) and with the promise that we will be unified at the conclusion. So while the stakes are high and potentially the success of the whole summer program lies in the decision, we can take our time, think things through, and rely on our cumulative wisdom to find a good solution. In this way, we can let emotions temper our decisions.

In an emergency, two things you don't have are time and the ability to come to consensus. You need a plan and a straightforward set of directions so that you can produce the most reliably good result that helps the most people and hurts the fewest. To prevent rash decisions you should bottle up your emotions during a crisis. Despite this, emotions have an important role to play in emergencies.

In general emotions are more useful in situations where there are multiple possible correct decisions, each with marginal benefits. We use a system of values to guide us in how to apply our emotion. If we feel strongly about something it may mean a particular solution’s marginal benefits should be chosen or discarded.

For 10 months spanning 2009 and 2010 a friend and I prepared for a 5-week trip to the Alaskan Bush. We weighed gear, compared caloric contents of various substances, and read volumes on wilderness survival and Alaska. We also created an emergency plan. We listed as many potential emergencies as we could, and then, from the calm of our own computers thousands of miles apart, debated and doctrinized our responses. This method allowed us the chance to inject emotion and values into our emergency responses without accessing that emotion during the emergency. We had already agreed what we do if one of our backpacks gets washed downstream, or if some of our food spoiled. This meant that as frustration or anger or hunger clouded our vision on the trip, we would still have the tempered response available.

Sunday, January 1, 2017

A Retrospective Resolution - Carrying Around Luggage

Last year my New Years' Resolution was to make use of Scott Arizala's

wisdom about unloading buses. As a camp director for years he had been

frustrated by the lack of coherence and organization at his camp as kids

arrived on buses and their stuff was carted to their cabins. While the kids were doing get-to-know-you activities and eating dinner, the bags would all be brought to cabins. One or two

kids would "lose" their stuff for hours every week.

Scott hated how unwelcome it made the kids feel when they walked into their cabin and couldn't find their bag. For years he would remind staff on change day to be careful with the bags, but would spend his day all over camp while someone else coordinated the bag moving. It all changed when he got in the face of one young counselor who had made a mistake and the counselor cheekily replied: "If you care so much about the bags, why don't you do it."

So for the rest of the summer and all the years since, Scott has directed camp from the parking lot on change days. Personally welcoming every camper, and making sure no one's stuff gets lost. It may be a little trickier to deal with problems that arise with just a radio and a quick wit, but the kids feel welcome.

The lesson he taught (and I tried to internalize) was twofold: As a manager you have limited time, you can't be in charge of everything, and have to balance which things you do based on what needs to get done and what will give you satisfaction to complete. Secondly and more importantly, you will get better results from people if you realize that they may not care about the same things you do and calibrate your leadership accordingly.

Scott had many solutions available to him, and likely tried some or all of these:

In the end, he chose to take charge of the task himself. This past year, I tried hard to listen to myself when I got bitchy and either take charge of the project or task that was making me upset, try out an alternate method for fixing it like mentioned above, or let it go.

Scott hated how unwelcome it made the kids feel when they walked into their cabin and couldn't find their bag. For years he would remind staff on change day to be careful with the bags, but would spend his day all over camp while someone else coordinated the bag moving. It all changed when he got in the face of one young counselor who had made a mistake and the counselor cheekily replied: "If you care so much about the bags, why don't you do it."

So for the rest of the summer and all the years since, Scott has directed camp from the parking lot on change days. Personally welcoming every camper, and making sure no one's stuff gets lost. It may be a little trickier to deal with problems that arise with just a radio and a quick wit, but the kids feel welcome.

The lesson he taught (and I tried to internalize) was twofold: As a manager you have limited time, you can't be in charge of everything, and have to balance which things you do based on what needs to get done and what will give you satisfaction to complete. Secondly and more importantly, you will get better results from people if you realize that they may not care about the same things you do and calibrate your leadership accordingly.

Scott had many solutions available to him, and likely tried some or all of these:

- He could have added an object lesson to his staff training by having several of his staff's possessions get "lost" en route to a staff trip and then getting them to talk to the rest of staff about what that felt like (thus increasing staff motivation to do a good job with the bags).

- He could have created or helped another staff member create a more organized method for bag moving - like drawing chalk lines in a grid on the pavement for each cabin (thus adding agency to a staff member).

- He could have organized the registration communication with parents to include a request for color coded tape/ribbon on each bag depending on the child's cabin (thus showing parents his camp cared how their possessions were treated).

In the end, he chose to take charge of the task himself. This past year, I tried hard to listen to myself when I got bitchy and either take charge of the project or task that was making me upset, try out an alternate method for fixing it like mentioned above, or let it go.

Thursday, December 8, 2016

Conflict and Growth

People grow through conflict and discomfort. I was reminded of this recently by a Facebook post showing a lobster shedding its shell only when it grew too big and the pressure too high.

I spent a lot of time thinking about conflict while developing training modules for administrative and counselor training weeks at camp, and I have never come to a satisfactory conclusion about how to teach conflict.

When conducting exit interviews several months after the summer, each year one of the most cited examples of "staff issues" would involve a seminal argument in the staff lounge. I can't identify why it is that these conflicts hold so much power over people's perceptions, though I think there are several connected explanations:

First I think these arguments serve as a shorthand for other issues those people are already having. It's not that disagreeing about feminism (or change, or racism, or politics...) is all encompassing, it's that it embodies the laundry list of faults and unresolved disagreements each person sees in the other. When we don't like or get along perfectly with a person, we can use a public display of disagreement to justify those feelings even long afterwards.

Secondly I think people like things to be resolved. We like there to winners and losers, facts and liars, heroes and villains. When we can cast ourselves as heroically defending truth against some other, we feel good about ourselves. Many of the arguments that got cited were about topics that have no easy resolution, so to feel complete, we retreat to our well-worn opinions.

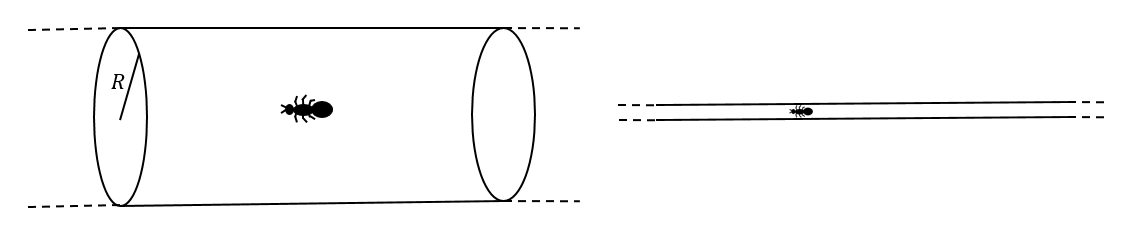

Thirdly I surmise that most people are bad at the process of conflict, and thus tend to see the argument at irreconcilably far from resolution when it is mostly a matter of viewpoint. I am reminded here of an example in a physics class I took in college that discussed string theory:

Imagine an ant on a power line that can travel along the wire or around it. For the ant those are two distinct dimensions. If we zoom out to street level, we can only observe the ant moving along the wire one way or the other.

Conflict is often zoomed way too far out. If we started in close by using conflict resolution skills like agreeing on what we agree on (usually arguments surround small fractions of things while the core principles are agreed upon), we would tend to see that there are many dimensions of agreement despite the one or two ways we disagree.

I spent a lot of time thinking about conflict while developing training modules for administrative and counselor training weeks at camp, and I have never come to a satisfactory conclusion about how to teach conflict.

When conducting exit interviews several months after the summer, each year one of the most cited examples of "staff issues" would involve a seminal argument in the staff lounge. I can't identify why it is that these conflicts hold so much power over people's perceptions, though I think there are several connected explanations:

First I think these arguments serve as a shorthand for other issues those people are already having. It's not that disagreeing about feminism (or change, or racism, or politics...) is all encompassing, it's that it embodies the laundry list of faults and unresolved disagreements each person sees in the other. When we don't like or get along perfectly with a person, we can use a public display of disagreement to justify those feelings even long afterwards.

Secondly I think people like things to be resolved. We like there to winners and losers, facts and liars, heroes and villains. When we can cast ourselves as heroically defending truth against some other, we feel good about ourselves. Many of the arguments that got cited were about topics that have no easy resolution, so to feel complete, we retreat to our well-worn opinions.

Thirdly I surmise that most people are bad at the process of conflict, and thus tend to see the argument at irreconcilably far from resolution when it is mostly a matter of viewpoint. I am reminded here of an example in a physics class I took in college that discussed string theory:

|

| https://brilliant.org/wiki/string-theory/ |

Conflict is often zoomed way too far out. If we started in close by using conflict resolution skills like agreeing on what we agree on (usually arguments surround small fractions of things while the core principles are agreed upon), we would tend to see that there are many dimensions of agreement despite the one or two ways we disagree.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)